Industry News Item

It's a (tentative) deal! I’m very happy to hear that there is now a tentative agreement between the WGA and the AMPTP. While there’s still ratification that has to occur before writers can go back to work, not to mention the ongoing SAG-AFTRA strike, but this is progress and I hope that the WGA got most of what they were asking for. Oh, and AMPTP and studio heads? You are terrible at your jobs if it took you this long to make a deal, do better and get a deal made with the actors ASAP. And don’t think we won’t forget about those executives who wanted to wait until writers started losing their homes; I’ve worked with great studio execs, terrible ones and everywhere in-between, but that was especially heartless and inhumane.

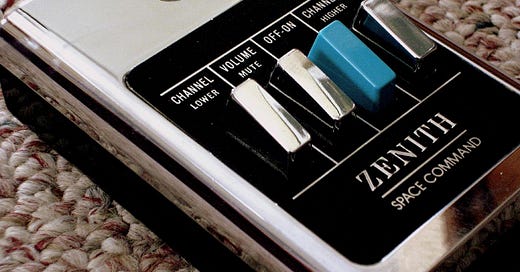

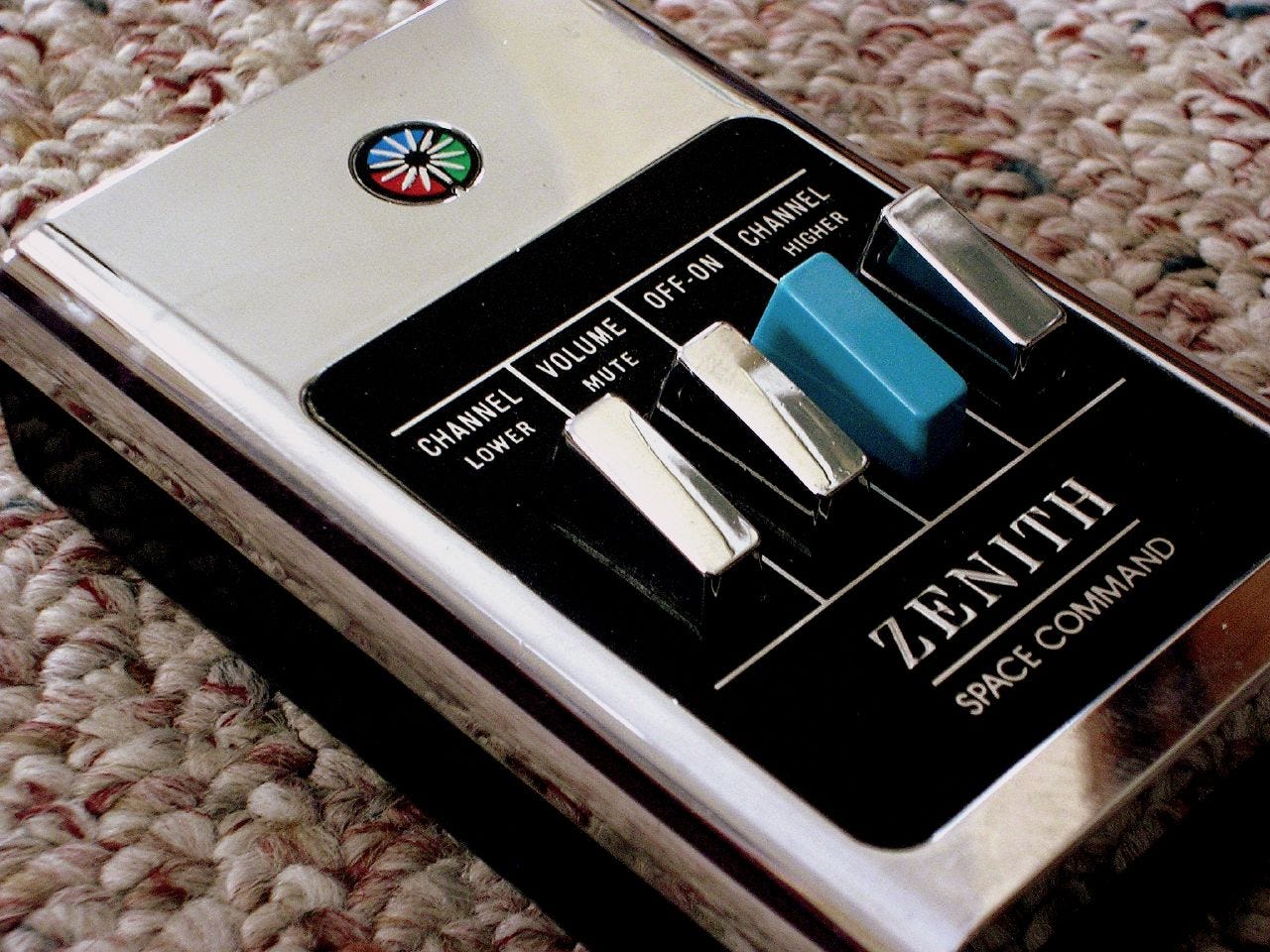

Now, not so much a news item, but a July article from The Verge about one of the first wireless television remote controls, the Zenith Space Command. We are all used to TV remotes working via infrared (IR) light, and some modern televisions and set-top boxes even use Bluetooth as the transmission medium between the couch and the screen. The Space Command, invented in 1956 by Robert Adler, was unique as that it did not rely on the electromagnetic spectrum to send commands, it used sound. Hence why television remotes are sometimes referred to as “the clicker”.

This marvel of mechanical engineering worked without batteries, utilizing the human holding it to generate the power needed through simple muscle action. Each key, when pressed, would strike an aluminum rod with a hammer, generating an ultrasonic tone. This inaudible (to humans, at least) tone would be picked up by the television set via microphone, which would complete the action. Each aluminum rod was a different length thereby producing different tones. Check out the article for more, especially Adler’s explanation of his thought process of why he landed on ultrasonic as his transmission method, which I found so practically and logically straightforward it was almost a thing of beauty.

Back, Back Through The Sands Of Time

Quick warning - today’s post has a metric crap ton of acronyms. I’ll do my best to define them, but it’s going to feel a bit like we’ve joined the military with the amount of alphabet soup being thrown around.

Chances are if you purchased a television in the last decade you probably made the leap from full high definition (HD) to what has been branded by TV manufacturers as ‘4K’ but is technically ultra high definition (UHD). Briefly, the difference between UHD and 4K comes down to resolution and aspect ratio. UHD is exactly four times the size of HD, with both sharing an aspect ratio of 16:9. This makes it easy for content filmed and framed for HD to keep the same appearance on an UHD display, just make it four times bigger, and you’re off to the races. The aspect ratio of 4K is 16:10, which means that content filmed and framed 4K will have tiny black bars at the top and bottom of an UHD display (referred to as letterboxing). TV manufactures decided to market their new tech as ‘4K’ or even more confusingly, ‘4K UHD’, which I continuously have to correct people at work when they use the terms interchangeably.

ANYWAYS…

I kicked this particular hornet’s nest not to talk about the history of UHD, but as a prelude to discussing the history of HD television. It goes back farther than you may think, and it leads up to a historic first that the industry seems to have forgotten. Let’s go all the way back to when electric television was first invented*.

There were numerous people who were working on the concept of the electric television but it was the work of Philo T. Farnsworth that made some of the crucial advancements in the early days of TV. In 1927 and 1928 his work had advanced enough that he was able to transmit and display simple images using his combination electro-mechanical television technology, and in 1929 he transmitted the first live human images, those of his wife Pem, using a fully electronic television system.

Early television was awash in different resolutions and technologies, and it was a combination of a series of patent disputes, the recovery from the Great Depression, and World War II that held back widespread television adoption during those decades. In the 1940s and 1950s there were finally standards that were implemented, but of course humans being humans they didn’t settle on a single standard. You might be familiar with the acronyms NTSC, PAL, and maybe even SECAM. These analog television broadcast standards divided up the countries of the world into three groups:

NTSC - National Television System Committee, which became the standard for North and Central America, parts of South America, and parts of Asia including Japan, South Korea and the Philippines. NTSC had 480 visible lines of resolution.

PAL - Phase Alternating Line, used in most of Europe, and parts of South America, Africa and Asia. PAL had 576 visible lines of resolution, 17% more than NTSC.

SECAM - Séquentiel de couleur à mémoire, French for color sequential with memory, used in France, Russia, and the remaining African and Asian countries that did not use either NTSC or PAL. It shares the same 576 visible lines of resolution as PAL but was harder to work with since it utilized frequency modulation, making linear editing difficult.

Indeed, it was the French who made the initial foray into what we now consider high definition. Throughout the 1940s, French television pioneer René Barthélemy demonstrated monochromatic broadcasts of 1015, then 1042 lines of resolution, and for a time the French used an 819-line standard (higher than the low end definition of HD, 720 lines of resolution) before moving to SECAM. For reference, modern HD has 1080 lines of resolution (that’s the horizontal part of 1920x1080, the resolution of full HD). The widespread adoption of color in the 1960s and early 1970s kept standard definition (SD) locked in for a while at 480 lines NTSC, 576 for PAL and SECAM.

Meanwhile in Japan during the 1960s and 1970s, broadcaster NHK began experimenting with higher definition than what the NTSC standard could accommodate. By the late 1970s the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE) had narrowed down potential HD television technology to four candidates:

EIA monochrome: 4:3 aspect ratio, 1023 lines, 60 Hz

NHK color: 5:3 aspect ratio, 1125 lines, 60 Hz

NHK monochrome: 4:3 aspect ratio, 2125 lines, 50 Hz

BBC colour: 8:3 aspect ratio, 1501 lines, 60 Hz

You’ll notice that none of these candidates match the specs of what we are used to in HD (16:9 aspect ratio, 1080 lines). These were also all analog technology, and with the move to digital broadcasting tech, and the US broadcasting standard moving from NTSC to ATSC (Advanced Television Systems Committee), the development of analog HD ended in the late 1980s.

Additionally, while the 5:3 aspect ratio (aka 1.67) was initially considered for digital HD, 16:9 (aka 1.78) was proposed and accepted as a compromise that would allow for both older TV content with a 4:3 (1.33) aspect ratio to fit in the center, and also film content in the commonly used 1.85 widescreen cinema format. If history had gone the other way, there’s a decent chance that our modern flatscreen TVs would be shaped more like squares than rectangles.

So What’s This Forgotten Historic First You Mentioned?

Thanks for sticking with me through all the technobabble. All of that was preamble to the television series I want to talk about today, The Secret Adventures of Jules Verne (2000).

TSAOJV, as I will now be calling it since I don’t feel like writing the entire title out over and over again, was a Canadian production that ran for a single season of 22 episodes, airing on CBC in Canada and The Sci-Fi Channel in the US. It followed the, well, secret adventures of a young Jules Verne, as he traveled the globe in a flying machine created by Phineas Fogg, Fogg’s cousin Rebecca, and his faithful servant Passepartout. It’s very steampunky, taking characters and situations from Verne’s writings and presuposing that they were based on actual events in the young writer’s life. Adversaries such as steam-powered cyborgs, rocket-propelled vampires and super secret societies really peppered the series with classic pulp adventure charm.

So why am I talking about yet another single season show (seems to be a running theme for the moment)? Because my friends, TSAOJV is the very first television show shot entirely on high definition video**. This is the one, the very first, and pretty much no one has ever heard of it. It’s not even culturally relevant enough to be a question on a pub quiz. And if you are curious enough to want to see what the world’s first ever television show shot entirely on high definition video looks like, I have some bad news for you - you can’t. It has never been released on physical media. No Blu-ray, not even on standard definition DVD. It’s not available for digital purchase. It’s not streaming anywhere. There are bootlegs floating around but they are likely sourced from SD broadcasts and suffering from duplication generation issues, which kind of defeats the purpose to trying to see it in its original, intended resolution.

Which is a travesty, frankly. Not because the actual content is amazing, from what I recall it isn’t. It was a fun steampunk romp that took a lot of big swings on things like CG locations on a 2000-era TV show, but missed the mark half the time. Why I think it’s a travesty is because of its technological historical significance.

Much like the history of film, the history of television is replete with gaps. From the format jump divide I mentioned in my last post, to cost-saving strategies like the BBC wiping their magnetic tape libraries for decades resulting in the loss of episodes of classic shows like Doctor Who, the fact that the first ever series fully produced in HD is not made readily available for academic and artistic study points to a real failure of the corporations that own all of this content in their duty of preservation.

Just because a studio believes that it wouldn’t be profitable to make some of their content available doesn’t mean it should remain locked away in some vault, or worse, lost forever as formats age and change. I could add to this rant by discussing issues with our copyright and public domain laws, as well as the lack of both leadership and incentive for studios to make more of their content available for non-profit reasons, but I think you understand my position on this.

Television is technology, television is art, television is culture, and when all three combine in just the right amount something special can happen. As the most recent ‘Golden Age of Television’ has shown us, some of the most culturally relevant stories today are told via the medium of television. Even when that magic doesn’t quite gel as in the case of The Secret Adventures of Jules Verne, failure to preserve something as historically important as the first television show entirely filmed in high definition robs us all of a small but important milestone in our shared history.

Go Watch This!

Warehouse 13 (2009-2014) - Since I can’t recommend TSAOJV due to it not being available anywhere, go watch this instead. Set in the modern day, this is about two federal agents, Pete and Myka, being reassigned to a warehouse where all the weird and dangerous artifacts go. Think if the ending of Raiders of the Lost Ark became a show, and a really fun one at that. Oh, and the video walkie-talkies they use? They’re called Farnsworths. Available on Blu-ray, DVD and digital storefronts

The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr. (1993) - Falling into the ‘weird western’ category, genre legend Bruce Campbell leads this single season series (yes, another one) investigating strange goings-on in the Old West. Aired on Fox during the 1993-94 season along with another freshman show you may have heard of called The X-Files. Available on DVD and digital storefronts

Legend (1995) - Remember UPN? This series stars a post-Star Trek The Next Generation John DeLancie and a pre-Stargate Richard Dean Anderson as a wacky inventor and a novelist pretending to be his own character Nicodemus Legend in the Old West (yes, another ‘weird western’), which should be catnip for all my 1990s sci-fi television nerds out there. Available on DVD and digital storefronts

Thanks for reading!

*For the purposes of this article I’m going to skip over the history of mechanical televisions, which is utterly fascinating (at least to me) but not relevant here we’re discussing HD and thusly the history of electronic television

**For camera nerds out there, the show used the Sony HDW-700, which according to the sales brochure I dug up via the interwebs, boasts “a newly designed CCD imaging system 1920x1080i” (cool), “same size and ergonomic design as the Digital BETACAM recorder” (um, okay), and “35mm film-like picture quality at a fraction of the cost” (the phrase ‘film-like’ is doing a LOT of heavy lifting here)